こんなの拾っちゃったよ

|

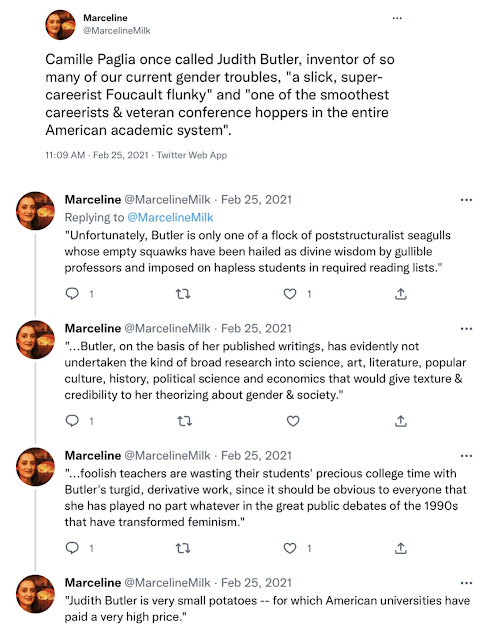

これはいかにもカミール・パーリアが言いそうなことだが、どこで言ってんだろうな、ネットで検索しても出てこないね。そのレトリックはまさにパーリア語法だが。 |

|

不幸なことに、バトラーは、ポスト構造主義のカモメの一群の一人に過ぎず、その空疎な鳴き声は、騙されやすい教授たちによって神の知恵として歓迎され、不運な学生たちに必読書リストを課している。 |

|

Unfortunately, Butler is only one of a flock of poststructuralist seagulls whose empty squawks have been hailed as divine wisdom by gullible professors and imposed on hapless students in required reading lists. |

|

愚かな教師は、バトラーの退屈で独創性のない仕事で学生の貴重な大学の時間を無駄にしている。 |

|

foolish teachers are wasting their students' precious college time with Butler's turgid, derivative work |

|

ジュディス・バトラーはひどく小さなポテトに過ぎないのに、そのためにアメリカの大学は非常に高い代償を払ってきたのだ。 |

|

Judith Butler is very small potatoes -- for which American universities have paid a very high price. |

・・・ノーコメント。

……………

次のものはいくらか穏やか系だ。アンドリュー・ウィルソンAndrew Wilsonという牧師の方の文。

彼は、私が何度か断片的に引用してきたカミール・パーリアの『フリーウーマン・フリーメン』の書評をしているんだが、神学系ゆえに、最後のパラグラフはーー私の観点からはーーいささか反論したくなるが、それ以外はパーリアのエッセンスを掴むためにきわめて優れた要約だね、少なくとも私はそう思う。

以下、主に機械翻訳だがそのまま掲げておく。

|

フェミニズムをフェミニストから救うこと:書評カミール・パーリア『Free Women Free Men』 By Andrew Wilson|2018年2月7日 |

|

Saving Feminism from the Feminists: A Review of Camille Paglia’s Free Women Free Men By Andrew Wilson | 7 February 2018 |

|

カミール・パーリアの『フリーウーマン・フリーメン』の挑発的な輝き。セックス、ジェンダー、フェミニズムは、そのタイトルから始まる。その意味は何だろうか。"free" という言葉は動詞なのか形容詞なのか? このタイトルは行動を促すものなのか(女性を解放せよ!男性を解放せよ!)、それとも現実に関する記述なのか(解放された女性は男性を解放する傾向がある)、それともその中間なのか(解放された女性、そして解放された男性)? 誰にもわからない。本書は1990年から2016年まで、芸術、文学、宗教、政治、倫理、哲学、歴史、法律、教育、ファッション、スポーツ、そして(最も顕著な)セックスなど、さまざまなテーマを扱っている。この本は、勇気があり、挑戦的で、時に腹立たしく、そしてしばしば眩しいエッセイ集であり、私が昨年読んだ中で、実際に火のアイコンを使うに値する唯一のテキストである。中絶賛成、ポルノ賛成、トランスジェンダー認定のフェミニストが書いた本なので、気弱な人には向かないかもしれないが、非常にお勧めだ。 どんな編集物でも要約するのは難しいが、この本のように多様で広範なものであればなおさらだ。とはいえ、『Free Women Free Men』が考えるに値し、格闘する価値のある7つの領域について紹介しよう。 |

|

The provocative brilliance of Camille Paglia's Free Women Free Men: Sex, Gender, Feminism begins with its title. What does it mean? Is the word "free" a verb or an adjective? Is the title a call to action (liberate women! liberate men!), or a statement about reality (liberated women tend to liberate men), or somewhere in between (liberated women, and liberated men)? Who knows? This sort of thought-provoking ambiguity runs throughout the pages of the book, the contents of which span a period from 1990 to 2016, and cover subjects as diverse as art, literature, religion, politics, ethics, philosophy, history, law, education, fashion, sport, and (most prominently) sex. It is a bracing, challenging, occasionally infuriating and frequently dazzling collection of essays, and the only text I have read in the last year that actually merits the use of the fire icon. Though not for the faint-hearted—it is written by a pro-abortion, pro-pornography, transgender-identifying feminist, after all—I highly recommend it. Summarising any compilation is difficult, and this is especially true with one as varied and wide-ranging as this. Nevertheless, here are seven areas in which Free Women Free Men is worth thinking about and wrestling with. |

|

1.この本は、20世紀フェミニズムのもう一つの系譜を提示している。私が知っているフェミニズムの物語は、第一の波(1790-1930:政治的・選挙的平等)、第二の波(1960-1980年代:リプロダクティヴ・ライツと職場での平等)、第三の波(1990年代-現在:多様性と個人主義、交差性)という単純な三つの段階があり、第二段階がすべて重要であると考えられている。パーリアは、この物語に2つの点で異議を唱えている。 第一に、第二の波のフェミニズムの重要性が劇的に誇張されていることを示し、この時代の女性の権利の向上は、ブラを燃やす抗議行動や女性グループよりも、第二次世界大戦、テクノロジーの発展(洗濯機、タンブル乾燥機、避妊ピル)、ポップカルチャーの出現(ハリウッド、ビートルズマニア、スウィング60年代のロンドン)によってはるかに促進されたと主張している。 第二に、彼女は、ベティ・フリーダンやグロリア・スタイネムからケイト・ミレットやアンドレア・ドウォーキンまでではなく、キャサリン・ヘプバーンやシモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールからバーバラ・ストライサンドやダイアナ・リグ、ラクエル・ウェルチといった60年代のアイコンを経て、マドンナやパーリア自身といった現代の「親セックス」フェミニストまでの「反体制派」の系統をたどっていることだ。本書には、「私はフェミニストからフェミニズムを救いたい」というシンプルな宣言があるように、さまざまな点での利害関係が存在するが、そのニュアンスと区別は有用である。 |

|

1. It presents an alternative genealogy of twentieth-century feminism. The feminist story I know has three simple phases—first wave (1790-1930: political and electoral equality), second wave (1960s-1980s: reproductive rights and workplace equality), and third wave (1990s-present: diversity, individualism and intersectionality)—with the second phase regarded as all-important. Paglia challenges this narrative in two respects. First, she shows that it dramatically overstates the importance of second wave feminism, arguing that the advance of women’s rights in the period were far more driven by World War II, developments in technology (washing machines, tumble dryers, the contraceptive pill) and the emergence of pop culture (Hollywood, Beatlemania, Swinging Sixties London) than they were by bra-burning protests or women’s groups. Second, she traces the lineage of her “dissident feminism,” not from Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem to Kate Millett and Andrea Dworkin, but from Katharine Hepburn and Simone de Beauvoir, via sixties icons like Barbara Streisand, Diana Rigg and Raquel Welch, to contemporary “pro-sex” feminists like Madonna and Paglia herself. There is plenty of score-settling here—at one point, she announces very simply “I want to save feminism from the feminists”—but the nuances and distinctions are helpful nonetheless. |

|

2.その際、現代のフェミニズム、とりわけパーリアがそのキャリアを通じて反対してきた反男性、反セックスという表現に対して、内部からの強力な批判を提供している。歴史的に見れば、フェミニズムは、その指導的哲学が自明であるかのように語り、その歴史的偶発性と、特に三つの哲学的・文化的発展への負い目を認識することに失敗してきたと、彼女は主張する。(また、美学、生物学、心理学に対する理解も不足していると彼女は主張するが、それはまた別の話である)。現代のフェミニズムの背景にあるのは、1950年代の家庭生活におけるブルジョワ的な退屈さである(『マッドメン』など)。 男性が戦地にいる間、女性は工場の仕事を引き継がなければならなかった。上腕二頭筋を鍛えるロージー・ザ・リベッターの全盛時代である。しかし、退役軍人が戻ってくると、女性たちは退くことを期待された。しかし、第二次世界大戦後、男女ともに普通の家庭生活を求めるようになった。家庭の問題がクローズアップされ、男女の役割分担が見直されたのである。また、結婚式が盛んに行われるようになり、それにつれて出産も盛んになった。1940年代後半から50年代にかけては、映画、テレビ、広告などで、母性、主婦性が女性の最高の目標であるかのように宣伝された。第二波フェミニズムが、正しく立派に反発したのは、この同質性だった。しかし、あまりにも多くの第二波フェミニストが、その不満を外挿し、あらゆる場所、あらゆる歴史の中で、すべての男性を非難するようになった。言い換えれば、第二波フェミニズムのイデオロギーは時代と場所を特定したものであった、あるいはそうであるべきだったのだ。戦後の家庭内事情は、比較的ローカルな現象であった。問題は性差別だけではなく、労働者階級の拡大家族から中産階級の核家族への産業革命後の社会進化であり、女性は快適な家庭の中で痛ましいほど孤立していたのである。 教会内の議論との類似性については、ここでいろいろとコメントしたいのだが、それはTHINK会議を待つしかないだろう。 |

|

2. In doing so, it provides a powerful critique from within of contemporary feminism, particularly its anti-male, anti-sex expressions which Paglia has opposed for her entire career. Historically, she argues, feminism has talked as if its guiding philosophy is somehow self-evident, and failed to recognise both its historical contingency and its debt to three philosophical and cultural developments in particular: the Western tradition of civil liberties, capitalism and the industrial revolution, and religion. (It has also, she argues, deficient in its understanding of aesthetics, biology and psychology, but that’s another story.) The bogeyman in the background for contemporary feminism is the bourgeois boredom of 1950s domesticity—Mad Men, anyone?—but the particularity of this cultural moment has been neglected, and its constraints universalised to all generations everywhere: While men were at the front, women had to take over their factory jobs: this was the heyday of Rosie the Riveter, flexing her biceps. But when the veterans returned, women were expected to step aside. That pressure was unjust, but after World War Two, there was a deep longing shared by both men and women for the normalcy of family life. Domestic issues came to the fore, and gender roles repolarized. With so many weddings, there was an avalanche of births—the baby-boomers who are now sliding downhill towards retirement. In the late 1940s and ‘50s, movies, television, and advertisements promoted motherhood and homemaking as women’s highest goals. It was this homogeneity that second-wave feminism correctly and admirably rebelled against. But too many second-wave feminists extrapolated their discontent to condemn all men everywhere and throughout history. In other words, the ideology of second-wave feminism was or should have been time- and place-specific. Post-war domesticity was a relatively local phenomenon. The problem was not just sexism; it was the postindustrial social evolution from the working-class extended family to the middle-class nuclear family, which left women painfully isolated in their comfortable homes. There are all sorts of comments we could make here about the parallels with debates within the church, but these will have to wait for the THINK conference. |

|

3.パーリアは、「平等なフェミニズム」、すなわち法の下での両性の平等と社会における両性の平等と、「女性への特別な保護」を峻別しており、それは本質的に幼児化するものと考えている。(これは、「機会の平等」と「結果の平等」の区別と全く同じではないが、明らかに類似している部分が多い)。彼女が最近紹介したジョーダン・ピーターソンを彷彿とさせるように、彼女は、男性が抑圧的だから男性優位の環境がそうであると決めつけることを嫌い、男性が競争するのに対し、女性は特別扱いを期待するからそうなるのかもしれない、と示唆している。ある章のタイトル、"Coddling Won't Elect Women "を読めば、そのことがわかるだろう。 |

|

3. Paglia distinguishes sharply between “equity feminism,” that is the equality of the sexes before the law and in society, and “special protections for women,” which she regards as inherently infantilising. (This is not quite the same as the distinction between “equality of opportunity” and “equality of outcome”, but it has a number of obvious similarities to it.) In a manner reminiscent of Jordan Peterson, whose recent book she blurbed, she is loath to assume that male-dominated environments are such because men are oppressive, and suggests that they may be such because men compete, whereas women expect special treatment. The title of one chapter, “Coddling Won’t Elect Women,” will give you an idea. |

|

4.彼女はまた、女性学に対する鋭い批判を行い、ピーターソンをその擁護者のように見せている。「女性学は、集団思考に異議を唱えない、居心地の良い、仲の良い泥沼である・・・。彼女たちの政治は、感傷的な空想と裏づけのない言葉のカテゴリーからなる流行の組織である。自分たちの特権に対する罪悪感が、彼らの政治的言説を特権対剥奪という単純化された世界のメロドラマに凍りつかせたのだ」。半世紀にわたるフェミニストの執筆活動から生まれた現代の古典は、60年以上前のもの(シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールの『第二の性』)しかないのである。「女性学は制度化された性差別である......。"ジェンダー "は今や社会構築主義のための偏った、慎重なコードネームである。そこで働く女性たちは、単に普通の女性とは違っていて、全国的にも世界的にも、彼女たちを代表しているわけではないのだ。「学究的なフェミニストは オタクの読書家の夫が 人間の理想的な男性像だと考えている」。 |

|

4. She also gives such a trenchant critique of Women’s Studies that she makes Peterson look like an apologist for it. “Women’s studies is a comfy, chummy morass of unchallenged groupthink ... Their politics are a trendy tissue of sentimental fantasy and unsupported verbal categories. Guilt over their own privilege has frozen their political discourse into a simplistic world melodrama of privilege versus deprivation.” There is only one modern classic to have emerged from half a century of feminist writing, and it is now over sixty years old (Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex). “Women’s studies is institutionalized sexism ... “gender” is now a biased, prudish code word for social constructionism.” The women who work there are simply not like ordinary women, and do not represent them, either nationally or globally: “academic feminists think their nerdy bookworm husbands are the ideal model of human manhood.” |

|

西洋文学の正典を再構成する試みは、それを凡庸にすることにしか成功していない。「歴史は異性愛者の白人男性によって書かれ、女性を組織的に抑圧してきたことから、知られざる女性の天才が再発見されて正典に復帰するのを待っているという主張が常になされてきた。現代のフェミニズムのこの前提は、最初から感傷的な幻想だったのだ」。ジェンダー研究部門は、大学が女性教員を増やしたいから存在しているだけの、利己的なカルテルで構成されている。「真の左翼は主要大学には存在しない」。ブルジョア的なアームチェア・アカデミズムはどこにでもあり、「保育園キャンパス」が存在するのだ。ジュディス・バトラーは 「独創性なく無学」だ。フーコーとラカンは衝撃的なほど過大評価されているが、その主な原因は歴史に対する無知である。「生まれたばかりのアヒルが掃除機を見たら、それを母親だと思うようなものだ。そういうことだ。フーコーは、みんなが追いかけた掃除機である」。あるいは、もっと無粋な言い方をすれば次のようになる。 「女性学は、下品な人、不器用な人、泣き虫な人、フランスかぶれな人、御用学者な人、お調子者の人、絵空事のユートピア主義者、いじめっ子で聖人ぶって説教する人たちがごちゃ混ぜになったものである。理性的で穏健なフェミニストたちは、ファシズムに直面しても、善良なドイツ人のように沈黙を守っている......。ジェーン・ハリソンやギゼラ・リヒターのような偉大な女性学者は、男性的な古典の伝統の知的規律によって生み出されたのであって、粘着質ですべてを許す姉妹関係の気まぐれな感傷主義によって生み出されたのではない、そこからはまだ一流の本が生み出されていないのである。 (私は知っている)。 |

|

Attempts to reconfigure the canon of Western literature have only succeeded in rendering it mediocre: “The claim has constantly been made that history was written by heterosexual white men and that, given the systematic suppression of women, there are unacknowledged female geniuses waiting to be rediscovered and restored to the canon. This premise of contemporary feminism has been a sentimental illusion from the start.” Gender Studies departments consist of a self-serving cartel that only exist because universities wanted to increase the number of female faculty members. “Authentic leftism doesn’t exist in our major universities”; bourgeois armchair academics are everywhere, and we have “the nursery school campus.” Judith Butler is “derivative and unlearned.” Foucault and Lacan are shockingly overrated, largely due to ignorance of history: “It’s sort of like ducks when they’re born—if they see a vacuum cleaner, they think it’s their mother. That’s what happened. Foucault is the vacuum cleaner that everyone followed.” Or, even less tactfully: |

|

Women’s studies is a jumble of vulgarians, bunglers, whiners, French faddicts, apparatchiks, doughface party-liners, pie-in-the-sky utopianists, and bullying, sanctimonious sermonizers. Reasonable, moderate feminists hang back and, like good Germans, keep silent in the face of fascism ... Great women scholars like Jane Harrison and Gisela Richter were produced by the intellectual discipline of the masculine classical tradition, not by the wishy-washy sentimentalism of clingy, all-forgiving sisterhood, from which no first-rate book has yet emerged.(I know.) |

|

5.また、パーリアは、すでに十分な問題を抱えていなかったかのように、強い男性の存在を擁護し、賞賛さえしている。競技場は、レヴェリングアップ(女性がオープンに男性と競い合う)か、レヴェリングダウン(男性がオープンな競争を控え、印象的なフレーズで「女性に自分の砂場を作ってそこで遊ばせる」)によって平らにすることができるが、彼女がどちらのオプションを好むかは想像に難しくない。西洋文明は男性によって築かれ、現在も男性(特にその体力)によって支えられていると彼女は主張する。しかし、西洋のエリートたちは、ブルジョワ的な価値観や文化、つまり事務職や管理職など、男性にできることは女性にもできることを優遇するため、ますます男性の強さを否定すると同時に、自らを養う手を噛むという壮大な見せかけをするようになっている。しかし、世界は常にこのようであったわけではないし、今後もそうであろう。「次の黙示録の後では、男性が再び必要とされるでしょう」。また、デスクワークの人たちが考えているように、現在でも男性の肉体労働から解放されているわけでもない。「道路を作り、コンクリートを流し、レンガを積み、屋根にタールを塗り、電線を張り、天然ガスや下水管を掘り、木を切り払い、宅地開発のためにブルドーザーを使って景観を変えるなど、汚くて危険な仕事をするのは圧倒的に男性である......。広大な生産と流通のネットワークを持つ現代経済は、男性の叙事詩であり、女性はその中で生産的な役割を担ってきた。しかし、女性はその原作者ではない。確かに、現代の女性は十分に強く、賞賛すべきところは賞賛しうる」。 この現実は、否定されることもあれば、称賛されることもある、と彼女は主張する。なぜなら、「教養ある文化が日常的に男らしさや男らしさを否定していると、女性はいつまでも成熟する意欲も約束を守る意欲もない少年たちと一緒にいることになるから」。 |

|

5. As if she wasn’t in enough trouble already, Paglia also defends, even celebrates, the existence of strong men. Playing fields can be flattened by a levelling-up (women competing openly and holding their own against men), or by a levelling-down (men holding back in open competition, and saying, in one memorable phrase, “Let the women make their own sandbox and play in it”); no prizes for guessing which option she prefers. Western civilization, she argues, was built by men, and continues to be sustained by men (and their physical strength in particular). Yet increasingly it is denigrating the strength of men at the same time, in a spectacular display of biting the hand that feeds it, not least because Western elites privilege bourgeois values and culture—office jobs, managerial skills, and the like—in which women can do anything men can do. The world has not always been like this, however, and nor will it be: “After the next inevitable apocalypse, men will be desperately needed again!” Nor, in fact, is it as free from the physical labour of men as the desk-bound classes consider it to be even now: It is overwhelmingly men who do the dirty, dangerous work of building roads, pouring concrete, laying bricks, tarring roofs, hanging electric wires, excavating natural gas and sewage lines, cutting and clearing trees, and bulldozing the landscapes for housing developments ... The modern economy, with its vast production and distribution network, is a male epic, in which women have found a productive role—but women were not its author. Surely, modern women are strong enough now to give credit where credit is due! This reality, she argues, can either be denied or celebrated. But celebrating it is better not just for men, but for women as well, for “when an educated culture routinely denigrates masculinity and manhood, then women will be perpetually stuck with boys, who have no incentive to mature or to honor their commitments.” |

|

6.パーリアの性的差異に対するビジョンと強調は、驚くほど独創的であり、彼女はしばしば、私よりもはるかに二元的な言葉でそれを表現している。宇宙は男性と女性、空と大地、外から生命を肥やす雨と内から生命を育む大地で構成されている。前者は外側に焦点を合わせ、目に見える形で、後者は内側に焦点を合わせ、隠れる形で、子孫繁栄の象徴となる。前者はアポロ的で、秩序、構造化された力、硬い線といった男性の世界である。後者はディオニュソス的で、カオス、冥界の力、湾曲といった女性の世界である。男性は直線的でクライマックス的、未来に向かって前進し、女性は循環的、「同じ地点で始まり、同じ地点で終わる、循環的回帰の連続」である。美術史に関する注目すべき2つの章で、パーリアは、膨らんだ曲線と形のない体であるヴィレンドルフのヴィーナスと、なめらかな線と優雅な頭部を持つエジプトのネフェルティティの胸像を対比させている。「ヴィレンドルフのヴィーナスからネフェルティティへ:身体から顔へ、触覚から視覚へ、愛から判断へ、自然から社会へ」。この二人の女性は、その極端な違いにおいて、先史時代の女性の水のように球根のような暖かさと、古典時代の男性の氷のように数学的な定義の間の距離を表現しているのである。 |

|

6. Paglia’s vision of, and emphasis on, sexual difference is strikingly original, and she often expresses it in far more binary terms than I would. The cosmos is made up of male and female, the sky and the earth, the rain which fertilizes life from beyond and the land which nurtures life from within. The former’s procreative symbol is focused externally, and is visible; the latter’s is focused internally, and is hidden. The former is Apollonian: a male world of order, structured power, and hard lines. The latter is Dionysian: a female world of chaos, chthonian power, and curves. The male is linear and climactic, reaching forward into the future; the female is cyclical, “a sequence of circular returns, beginning and ending at the same point.” In a remarkable pair of chapters on the history of art, Paglia contrasts the Venus of Willendorf, all bulging curves and formless body, with the Egyptian bust of Nefertiti, all sleek lines and elegant head. “From Venus of Willendorf to Nefertiti: from body to face, touch to sight, love to judgment, nature to society.” The two women represent, in their extreme difference, the distance between the watery, bulbous warmth of the prehistoric female, and the icy, mathematical definition of the classical male. |

|

西洋文明は、グレコローマンとユダヤキリスト教をルーツとし、地球崇拝というより天空崇拝、ディオニュソス的というよりアポロ的である、と彼女は説明する。それは女性に対する男性の勝利、「腹の魔術」に対する「頭の魔術」、月に対する太陽、自然への屈服に対する超越、円に対する線の勝利を表しているのである。これはひどく女性差別的に聞こえるかもしれないが、女性はその恩恵を大いに受けてきたと彼女は主張する。 極東の象徴主義における男と女の同等性が、西洋における男尊女卑と同じように文化的に有効であったのかどうか、私たちは問う必要がある。どちらのシステムが最終的に女性により恩恵を与えたのだろうか?西洋の科学と産業は、女性を労働と危険から解放した。家事は機械がやる。ピルは生殖能力を無効にする。出産はもはや致命的なものではない。そして、西洋の合理性のアポロ的な線は、男のように考えることができ、不愉快な本を書くことができる現代の攻撃的な女性を生み出した。 |

|

Western civilization, she explains, with its Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian roots, is a sky-cult rather than an earth-cult, Apollonian rather than Dionysian. It represents the triumph of male over female, “head-magic” over “belly-magic,” sun over moon, transcending nature over capitulating to it, lines over circles. This might sound terribly misogynistic—but, she argues, women have benefited from it enormously: We must ask whether the equivalence of male and female in Far Eastern symbolism was as culturally efficacious as the hierarchization of male over female has been in the West. Which system has ultimately benefited women more? Western science and industry have freed women from drudgery and danger. Machines do housework. The pill neutralizes fertility. Giving birth is no longer fatal. And the Apollonian line of Western rationality has produced the modern aggressive woman who can think like a man and write obnoxious books. |

|

7.最後に、終末論である。パーリアの歴史観は、あらゆる帝国が永遠に続くと信じながらも、最終的には自らの重みで崩壊するというものだが、現在の文化的瞬間に対するその評価は、私のものよりもはるかにキリスト教的であることが多い。政治的なレベルでは、私はフクヤマの「歴史の終わり」というレトリックを信じたことはないが、文化的なレベルでは、世俗的、リベラル、寛容、民主的なポストキリスト教が、現在からイエスが戻るまでずっと続くと考えざるを得ない。だから、パーリアの現実的な説明は、歓迎すべき警鐘となる。 このような歴史への全面的なアピールは、文明の周期的な盛衰に関する歴史のはるかに暗い教訓を見落としている。地球上には、自分たちが永遠であると信じていた帝国の廃墟が散乱している。ワイマール・ドイツがそうであったように、ジェンダーの実験的浪費は時に文化的崩壊に先行する。後期ローマのように、アメリカもまた、ゲームやレジャーに気を取られた帝国である。今も昔も、英雄的な男らしさの崇拝が絶大な力を持つ狂信的な大軍が散らばり、国境の外で力を合わせているのである。 アウグスティヌス主義の影は、彼女のいくつかのエッセイに見られる。ローマ崩壊との明確な関連だけでなく、彼女の人類学(「歴史の恐怖と残虐行為は、人種差別、性差別、帝国主義のせいにできるところ以外は初等・中等教育から排除されてきた...しかし本当の問題は人間の本性にあり、宗教と偉大な芸術は、闇と光の力の間の戦争で永遠に引き裂かれると見ている」)にも表れている。進歩主義は、この2つの点で、重大な過ち、つまり、自らを必然的かつ永続的な存在、現代世界のオジマンディアスとみなす危険性をはらんでいる。 |

|

7. Finally, there is eschatology. Paglia’s view of history, in which every empire believes it will endure forever yet ultimately falls under its own weight, is actually far more Christian, in its appraisal of our current cultural moment, than mine often is. At a political level, I have never got anywhere near believing Fukuyama’s “end of history” rhetoric, but at a cultural level, I find it hard not to think of secular, liberal, permissive, democratic post-Christendom as a permanent fixture from now until Jesus returns. Which makes Paglia’s much more realistic account a welcome wake-up call: This sweeping appeal to history somehow overlooks history’s far darker lessons about the cyclic rise and fall of civilizations, which as they become more complex and interconnected also become much more vulnerable to collapse. The earth is littered with the ruins of empires that believed they were eternal ... Extravaganzas of gender experimentation sometimes precede cultural collapse, as they certainly did in Weimar Germany. Like late Rome, America too is an empire distracted by games and leisure pursuits. Now as then, there are forces aligning outside the borders, scattered fanatical hordes where the cult of heroic masculinity still has tremendous force. An Augustinian shadow can be detected in several of her essays, not only in the explicit connections she makes with the fall of Rome, but also in her anthropology (“the horrors and atrocities of history have been edited out of primary and secondary education except where they can be blamed on racism, sexism, and imperialism … But the real problem resides in human nature, which religion as well as great art sees as eternally torn by a war between the forces of darkness and light.”) Progressivism risks grave naivety on both counts, regarding itself as both inevitable and everlasting, the Ozymandias of the modern world. |

|

もちろん敢えて言うまでもなく『Free Women Free Men』には同意できない点が非常に多くある。ポルノ、売春、中絶、正当な性的表現、性的アイデンティティといったテーマについて私が彼女に抱く明らかな反対意見に加え、何かもっと深い問題があるのだ、これらの様々な枝葉が命を得るための根源が。それは、私が読む限り、彼女が本書で提示する数々のペア(空と地、雨と地、男と女、アポロスとディオニソス、高さと深さ、線と曲線、文化と自然、ペニスとヴァギナなど)は、対立、競争、衝突、暴力において永遠に続くよう定められているという概念である。非有神論的な見方では、これらは他の何ものでもないだろう。しかし、キリスト教的現実観においては、デイヴィッド・ベントレー・ハートが『無限の美』の中で示しているように、このような両極性は三位一体の神の生命の中で究極的に調和される。この生命には、同一性と分身、秩序ある高さと深さ、一と三、言と肉、美と崇高の双方が存在するのだ。したがって、男性と女性からなるこれらのペアは、避けられない競争ではなく、美しく補完的なものであり、天と地、神とイスラエル、キリストと教会の補完性、そして最終的な結合からその意味を引き出している。すなわち深遠なる神秘である。 |

|

There is an awful lot to disagree with in Free Women Free Men; that much, presumably, goes without saying. Alongside the obvious disagreements I have with her on subjects like pornography, prostitution, abortion, legitimate sexual expression, sexual identity and the like, there is something deeper that is amiss, a root from which all of these various branches draw their life. It is, as I read her, the notion that the numerous pairs she presents in the book—sky/earth, rain/land, male/female, Apollos/Dionysus, height/depth, lines/curves, culture/nature, penis/vagina, and so on—are shaped by, and destined to continue forever in, opposition, competition, conflict, even violence. Within a non-theistic outlook, how could they be anything else? In the Christian vision of reality, however, as David Bentley Hart shows in his (very different) The Beauty of the Infinite, polarities like these are ultimately reconciled within the life of the Triune God, in which we have both identity and alterity, ordered heights and chthonian depths, one and three, Word and flesh, the beautiful and the sublime. So pairs like these, from male and female on down, are not inescapably competitive but beautifully complementary, and draw their meaning from the complementarity of, and final union between, heaven and earth, God and Israel, Christ and the Church. A profound mystery, that. |